There are some new friends on this list since you last heard from me.

Hello and welcome to the several hundred who subscribed after reading my essay for The Free Press on Marshall McLuhan. I’m glad you’re here.

Another three hundred of you joined after encountering a thread I wrote about Yuri Bezmenov that got shared by Elon Musk. (Bizarrely, this was not the first time he’s engaged with my writing, but it was by far the biggest: 23 million impressions and counting.) If that’s what brought you here, thanks for signing up. I appreciate it.

My goal is to give you all more of what brought you here… and the unifying theme across them is the effect our media (and cultural) environments have on our individual minds.

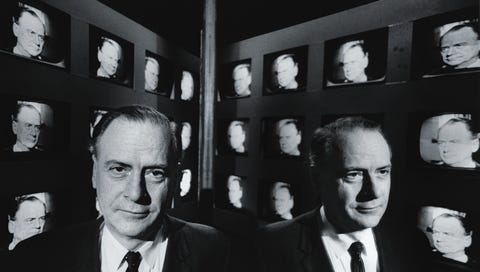

To start, I’d like go a little deeper into Marshall McLuhan, the great Canadian theorist of technology and media. (Two words that in his thinking represented much the same thing: a medium is any tool that extends our innate human capabilities, thereby changing us.)

McLuhan believed that different uses of our senses affected our thinking and being. Accordingly, I’ll give three slightly different ways of experiencing him: in print, in video, and in audio.

Finally, I’ll finish with 13 takeaways from his writing derived from my background research on all of this material.

Read

In the course of my research for the article on McLuhan for The Free Press, I read three or four of his books, listened to all of the recordings of him put out by the McLuhan Institute podcast, and watched pretty much every video of him available on YouTube. (A clip from one of these will appear below.)

I also contacted his grandson, Andrew McLuhan. He advised me to start with this article: an essay in Playboy magazine from 1969. (You’ll be amazed how long and erudite the article is; at its peak, Hefner’s magazine was more intellectually high-minded than any popular magazine today. The same issue features a Senator on gun control and sci-fi genius Arthur C. Clarke on space colonization.)

The piece offers perhaps the most useful and succinct encapsulation of McLuhan’s ideas.

You’ll find his playfulness, his seriousness, his verbosity, all on display for the bewildered and intrigued interviewer.

McLuhan: In the past, the effects of media were experienced more gradually, allowing the individual and society to absorb and cushion their impact to some degree. Today, in the electronic age of instantaneous communication, I believe that our survival, and at the very least our comfort and happiness, is predicated on understanding the nature of our new environment, because unlike previous environmental changes, the electric media constitute a total and near-instantaneous transformation of culture, values and attitudes. This upheaval generates great pain and identity loss, which can be ameliorated only through a conscious awareness of its dynamics. If we understand the revolutionary transformations caused by new media, we can anticipate and control them; but if we continue in our self-induced subliminal trance, we will be their slaves.

Watch

A year after this interview, when McLuhan was near the peak of his cultural influence, he sat with a friend and admirer, the bombastic stylist and urbane intellectual novelist, Thomas Wolfe.

Seated in aluminum lawn chairs, they have a wide-ranging conversation. One moment in particular grabs me: here, where Marshall proposes that all media — all of them — be “turned off” for a week as a grand experiment. This is the kind of policy idea I can get behind.

Listen

Listen to this recording of a 1968 Canadian show, which titled the episode “The End of Polite Society.”

In it, McLuhan describes the electric age as “much the greatest of all the human ages, there’s nothing even remotely to resemble the scope of human awareness” in it.

This appalls one of the other guests, the plummy British talk-show host Malcolm Muggeridge, who takes a much grimmer view of TV culture. The episode also features the pugnacious American writer, Norman Mailer.

13 Takeaways

Drawing from all this material and more, I’ve pulled the following observations (in no particular order) from my notes on McLuhan. A few may be paraphrases, most are my own riffs on his ideas. It would be difficult to chase down any precise genealogy. (So please don’t quote one of them elsewhere as “Marshall McLuhan says…” unless you find your own attribution.)

You cannot understand culture today without understanding technology. In turn, you cannot understand technology without understanding culture.

Most of our relationships with our people are now invisible. Instead of family reunions, we have family text groups.

Slang is a leading indicator of social change. Watch what words come and go—"Karen,” “based,” “black-pilled”—and you will see how perceptions are shifting.

We now have the means to keep everyone under surveillance at all times. As a result, one of the main objects of effort and expense in our civilization is simply watching what other people are up to in their “private” lives.

What matters is not what you say with your iPhone. It’s that whenever you have a question, your mind drifts toward your pocket, as if it’s a phantom limb (or phantom brain) connected to your body. This reflects how it’s changed you.

Constant change leads to a crisis in identity for individuals and societies. Mental disorders on the personal scale, and on the national scale, become more common because of the void this creates.

In the past, people had one lifetime. Later, it could be supplemented by books, which gave experiences of other lives in condensed form. Now, young people experience several lifetimes’ worth of sensation, experience, and thought by the time they hit puberty. Our educational systems poorly recognize and serve this reality.

If you look at human behavior, you will see that computers don’t serve us. We serve the computers.

The rate of history is now compressed. Because actions take place at the speed of light (mediated by our communications systems), the reaction is global and instantaneous. This means we again live in an age of myth: when demi-gods ruled the Earth.

“Politics offers yesterday’s answers to today’s problems.”

Social issues are not contained to their native societies. We have a sense of universal responsibility and universal involvement in each others’ lives.

The AI revolution represents the return of servants, with all the convenience, decadence, and danger this entails.

You are, in a real sense, living the lifestyle of an electron.

What I’ve Been Working On

For the last several months, I’ve been developing a new business with my partner, the bestselling author and journalist Geoffrey Cain. Previously, we’d both been working separately to help executives craft and write thought leadership.

With the creation of Alembic Partners, we’ve joined forces to maximize what we can do for clients.

We produce essays, thought leadership campaigns, and books, building up clients’ brands and platforms.

We’ve worked with CEOs, tech entrepreneurs, finance professionals, and ex-government officials, among others.

We’re still in soft launch (though already busy with client work). If you’re interested in learning more, drop me a line.

Hope you’re doing well in 2024,

Ben

It sounds like your new business is wrapped around bringing the art of integrating story craftsmanship and meaning to the leadership to enhance their brands. Interesting.

Wow - the Playboy essay was a true surprise! I am just reading through his lectures and interviews in "Understanding Me" and appreciated your distilled takeaways here. Looking forward to following more of your writing :)