How to Write Terribly

Don't plagiarize, but especially don't follow the same bad advice

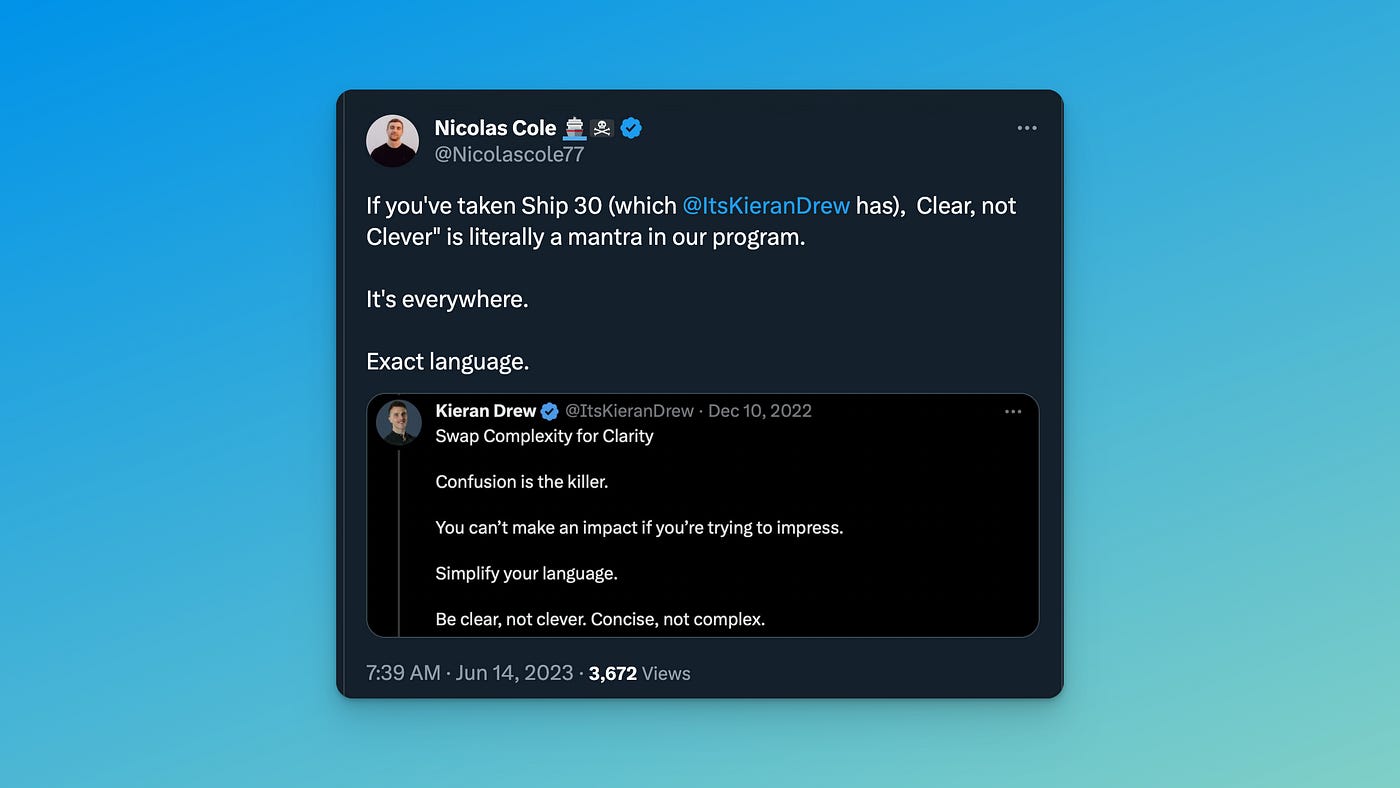

There was a small dust-up this week among Twitter’s self-anointed writing gurus.

One accused another (who had previously attended his program) of plagiarizing his writing advice.

His evidence was some identical phrasing:

Exhibit 1: “Specificity is the secret.”

Exhibit 2: “Clear, not clever.”

Putting aside the question of whether Guru 1 was ripped off (maybe), and whether it was wise to call out Guru 2 this way (no, it backfired on Guru 1), there is the more important question:

Whoever came up with it, is this writing advice any good at all?

Many defenders of Guru 2 pointed out that these allegedly borrowed phrases are ubiquitous.

“It’s self-evident. This is how you write well.”

“Everyone knows you need to be specific.”

“Everyone knows you need to be clear, not clever.”

But is that true?

I’ve been spending much of my reading time this week going through the books of Marshall McLuhan.

His writing is dense, elliptical, oracular, and full of wordplay.

It takes an effort to understand him.

When you do, he rewards you with wonderful insight.

The complexity of the syntax mirrors the complexity of the ideas. Here is from the first page of the introduction to Understanding Media.

“Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned. Rapidly, we approach the final phase of the extensions of man—the technological simulation of consciousness, when the creative process of knowing will be collectively and corporately extended to the whole of human society, much as we have already extended our senses and our nerves by the various media.”

This is one of his simpler statements.

If much digital writing is the equivalent of simple synth-pop melodies, McLuhan’s is a baroque fugue.

Here is another favorite writer of mine—a Nobel Prize winner Albert Camus.

His fiction is abstract, dreamlike, and spare in descriptors of place, physique, manner.

His prose achieves its hypnotic tone not by hammering hard details to make it “specific,” but rather by evoking effects.

The protagonist of The Stranger, Meursault, is never physically described.

Camus does describe the protagonist of The Plague, Dr. Bernard Rieux. Here is how he does it: Rieux is 35, of moderate height, dark-skinned, with short black hair.

Is that specific?

Or is it just enough to allow your imagination to fill in the character as you would like to see him?

In storytelling, hyper-specificity is the enemy of imagination.

It is often also the sign of an amateur writer.

You need to invite and involve the reader to complete your scenes.

I’d much rather read a difficult and clever writer than a clear writer without any cleverness in him.

Be as clever and complex as your talents allow.

Give just enough to ignite the reader’s imagination.

And if all the writing gurus on Twitter are giving the same pieces of advice, you might want to look elsewhere for inspiration.

Until the next time,

Ben

PS - There are better ways to get your writing noticed by the people who matter. If you haven’t already, you can check out my course for a simple method. And my sincere thanks to the many people who made the launch a success. It exceeded my hopes.

Makes me think about the timelessness of classic literature. Writing should make you think. And there may be a perfect middle, somewhere between the cleverness of McLuhan and the boring clarity of self-proclaimed Twitter gurus. To me, Steinbeck exemplifies that. His language is so simple. Reading at the surface level is fine and the story unfolds before you. But there is so much meaning underneath for the reader willing to dig deeper.

Great advice, and definitely something to chew on. Thanks 👍🏼