Three people stand before a window.

They look out over the same landscape.

One turns to the other, “I see a storm coming.”

The other one looking into the near distance declares, “I see a boat bringing goods to shore. I wonder if it will have what I’ve been waiting for.”

And the third speaks: “This window is dirty. Don’t you have any self-respect to clean it?”

When you write, it often feel something like this. You create a window onto yourself, your views, your world, and invite people to look through it.

You hope to educate, please, delight, inform, or perhaps galvanize to action.

But perception is an active process. Your readers do not simply ingest your words and acquire your ideas, like the Pill of Murti-Bing described in Polish poet and dissident Czeslaw Milosz’s masterpiece on ideological conversion, Captive Mind.

Your audience brings their own assumptions and experiences to the act of reading.

When they look through the window of your writing, half of what they see is their own reflection in the glass.

Take a sentence that looks clear and simple. People interpret it countless ways.

In Matthew 5:44, Jesus says: “But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.”

Does this endorse pacifism? Stoic detachment? Enlightened otherworldliness? Muscular self-confidence? Just war?

Even your family texts and work emails run into this. It’s not simply what you say. It’s how you say it; and just as often how you didn’t say it.

Did you use emojis? Exclamation marks? Was the response too short? Too long? Do you use too many gifs? Not enough?

Every detail is fodder for interpretation.

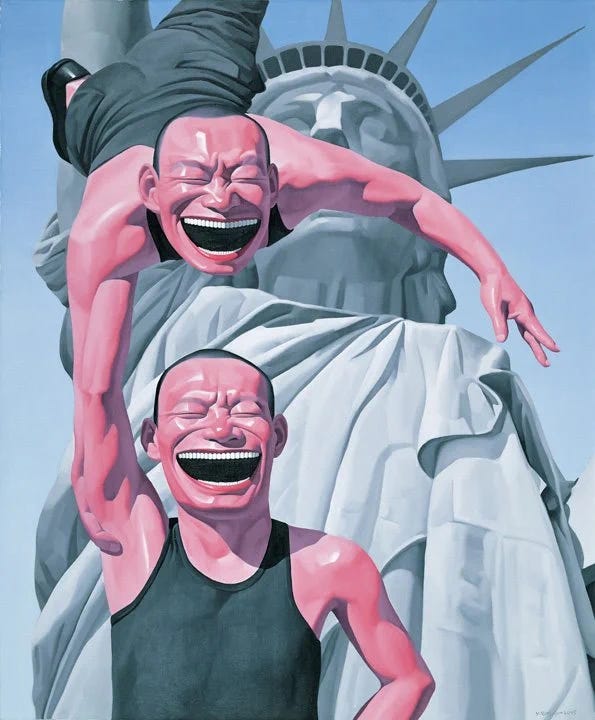

This has been on my mind this week because a thread I wrote on China got widely read, and as often happens, the interpretations ranged as widely as the readers.

While I was grateful for many positive responses, I was surprised by those who seemed to miss what was (in my mind) the real point: it isn’t really “about China.” (A place I love in many ways, above all for the people.) It’s about human nature. How do people anywhere respond to tightening limitations in what they can say and do? What goes for China, goes for America, too.

(I’m aware that a number of you have joined this newsletter because of it, and I thank you for signing up. Welcome to the community.)

A certain amount of misunderstanding is inevitable with any work of writing.

You are, after all, a mirror.

Your job as a writer is to polish the glass.

What I’m Working On

One of the best ways to improve as a writer is to do it in a supportive community.

For those looking to make writing a public part of your life, I encourage you to explore the program Write of Passage. I know several people who say it’s one of the most transformative things they’ve done.

Several of you have signed up, and I’m excited for you. If it interests you, the window closes on Tuesday. You can sign up here to join the cohort.

Beyond that, there’s a new project in the works that I’m looking forward to sharing with you soon. A collaboration.

What’s your experience with being understood or misunderstood as a writer?

Until the next time,

Ben

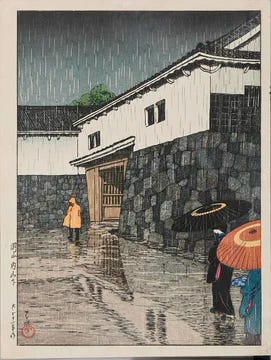

PS - The story of the ex-McDonald’s shift worker, Sheehan, who has since gained a massive following as the Twitter writer “Cultural Tutor,” is worth checking out. Scroll down to the bottom. Below, an image from a great thread of his recently on the Japanese painter of atmospherics, Hasui Kawase.

Thank you. Beautiful sentences:

"But perception is an active process. Your readers do not simply ingest your words and acquire your ideas.Your audience brings their own assumptions and experiences to the act of reading. When they look through the window of your writing, half of what they see is their own reflection in the glass."

“Every detail is fodder for interpretation.

A certain amount of misunderstanding is inevitable with any work of writing.

You are, after all, a mirror.

Your job as a writer is to polish the glass.”

Thanks for writing this. It somehow feels like both the goal and the purpose.