The Parable of the Left Hand Brick

9 Final Lessons From Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

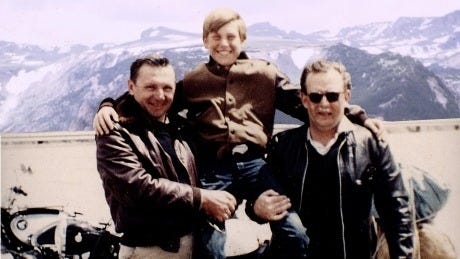

In my last letter on Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, I had finished re-reading the first third of this wonderful book. At that point, the story had not dug into the book’s major theme—Quality—and the sense of foreboding, of mounting menace, had not appeared.

This letter will finish the book.

For those who have not read ZAMM (which I encourage you do to), I’ll refrain from revealing too much of the plot. But suffice it to say that the narrator is not all he seems. And as the book proceeds, the reader becomes increasingly anxious about his relationship with his son.

Why is the narrator so brusque? So clipped and cold? Why does he refuse to answer questions with anything more than the barest detail?

(For the sake of convenience, I’ll refer to the narrator as “Pirsig,” since the story is modeled on aspects of the author’s life.)

The book, which begins as a road-trip adventure across the Great Plains, gradually becomes a tale of an estranged father and son quietly tormenting one another with unspoken grievances and memories lost or suppressed in the past.

A large chunk of the middle of the book is given over to Pirsig’s ideas on Quality. (Always capitalized — a tactic which I’ll return to in a moment.) This section of the book is absorbing and challenging; it is deep and worthwhile; it seems to be, from Pirsig’s notes, the stuff he really wished to convey to readers. The book came about because he wanted to write a philosophical essay, but he realized he needed a novel to carry it.

The funny thing is, the novel he built to carry the essay ends up being better than the essay itself.

Others may disagree with me. PhDs have been written on Pirsig’s ideas. Quality is Pirsig’s concept for the Tao, the Buddha, and God, and he builds a cathedral of reason out of this concept. While I enjoyed visiting the cathedral, I did not want to live there. At this point in life, I already have a metaphysical house (so to speak) where I dwell.

This is one difference reading the book a second time. As Heraclitus said of rivers, so it is with books: no man can step in the same river twice. The first time I followed Pirsig and son across the Midwest, I was swept away with the ideas. It was my first real exposure to philosophy. The second time, the philosophy left me cold, but the emotions of the book—above all the growing tension between father and son—moved me.

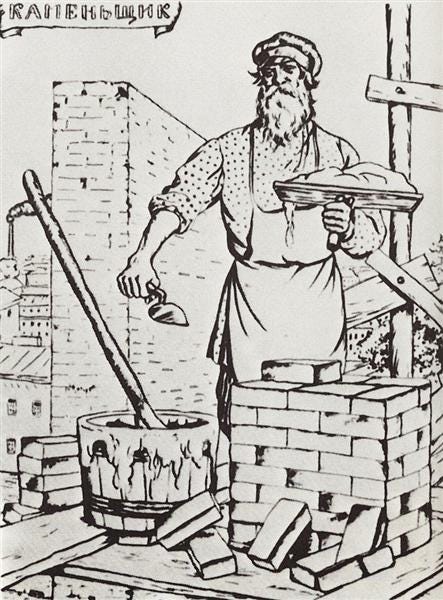

The Parable of the Left Hand Brick

In the latter 2/3 of this book, there are many lessons for creators—too many. The best of the ones I jotted down are below. But perhaps the most striking and important one I’ll call the Parable of the Left Hand Brick.

In the book, the narrator remembers teaching a struggling student how to write. When asked to produce an essay of 500 words, she proposes to write about America.

Taken aback by the breadth of her subject, and knowing it will fail to yield a good essay, the narrator encourages her to pick a slimmer topic.

“Focus on Bozeman, Montana.”

When she fails to write a single word, he narrows it further.

“Try the main street of Bozeman.”

Still nothing.

“He was furious. ‘You’re not looking!’ he said. … The more you look the more you see. She really wasn’t looking and yet somehow didn’t understand this.

He told her angrily, ‘Narrow it down to the front of one building on the main street of Bozeman. The Opera House. Start with the upper left-hand brick.’”

The next class, she turned in 5,000 words.

The story captures a twofold truth about creating—and thinking. First, if you set your sights on too large a subject, you’ll never find a foothold. You need to take on something small. Second, it’s important to make sure you’re not just repeating what others have already said. That is, you must see for yourself.

The best way to do that is to choose a topic where you simply have nothing else to draw on. Only your senses. Then you’ll see it fresh.

How to Find Your Brick

In any story you tell, start with the small and specific. It should probably seem too trivial to be worth your attention.

For example, your brick could be the squeaky elevator in the building where you launched your company. It could be the odd nickname your uncle gave his dog. Or the trampled corsage on the ground outside your son’s high school on graduation day.

Whatever it is, it should force your attention on something that you have directly experienced. The one memory, the one image, the one chart, the one anecdote. Break it down until you can hold it. Then build your story up again from there.

This discovery is what enabled the student in ZAMM to “look and see freshly for herself, as she wrote, without primary regard for what had been said before.”

Whether your goal is growing a newsletter or launching a fund, your communications need to start with that specific, single thing.

The brick.

9 More Lessons for Creators

I filled the margins of ZAMM with notes. Moments where the craftsmanship was uncanny, or moving, or surprising.

Overall, I came away from my second reading convinced that ZAMM is a rare and special masterpiece. It has little patience for the conventions of standard fiction. There are few characters, little action (apart from riding a motorcycle, taking a hike, and eating hamburgers), and almost no interpersonal drama.

Instead, you have a father and son riding on a motorcycle, quietly thinking about the past; until at last the memories that have haunted them erupt into the open, causing one of the most dramatic reversals in fiction that I’ve ever seen. The ending doesn’t merely change your sense of the narrator; in an instant, it changes how you perceive the entire 400 pages of the book that have come before. It’s a huge release of tension, right at the end, giving the reader a great catharsis.

With all that, here are the techniques to consider borrowing in your next work:

To Ground Your Ideas, Go on a Journey Through Space and Time. When you’re dealing in abstract or subtle ideas, present them as waypoints on a journey. Take your audience on a hike, or a walk, and use this device to unfold a “huge structure of thought.”

Make Language Weird. Pirsig is known for his ideas about Quality. One small but meaningful reason why he’s known for it is that capital “Q.” It takes the word out of ordinary usage, and forces you to stop and reconsider it. When you have an original idea, give it a weird look, and people will pay attention.

Follow Your Obsessions. If you ever feel like your interests are too dull to share, just remember that Pirsig made a bestseller out of extensive passages on motorcycle repair. Your enthusiasm is what matters. That’s what will carry the audience along.

Keep Secrets. Nothing teases an audience more—and pleases them—then being shown something mysterious that the author refuses to explain—yet.

Repeat Yourself. The reader loves a refrain. Introduce a theme, and then bring it back. Pirsig does this at the structural level, by returning regularly to different themes: the motorcycle, his son Chris, the ideas of Quality.

Show Empathy to Your Audience. If you have tough material to share, acknowledge it. Show that you understand your audience during the hard parts of a story. During the long sections on Quality, Pirsig occasionally has the narrator comment on how slow and arduous the journey is. But don’t deprive readers of the hard parts. Journeys that are worth going on must be hard.

Strategically Change the Rules. Once your story is going, at a carefully chosen moment, break with the pattern you’ve set. Change what’s allowed. This is one of the most powerful ways to create a feeling of delight. ZAMM does this spectacularly at the end. (When the narrator suddenly changes into… well, you should read it.)

Reveal the Secret. A revelation at the climax, especially one that calls back to a theme in the beginning of the work, is incredibly powerful.

Bring About a Great Return. At a key moment, bring back a forgotten theme, person, or idea. The resolution of a long simmering tension gives a magnificent release.

What I’m Working On

As previewed in my last email, I’m moving mostly off of Substack, and this is the last email from this provider for now. You’ll hear from me next from ConvertKit. (Hopefully you won’t even notice the difference.)

And as a heads up, in addition to client work, I’m currently working on a course for people to build up their digital profile to attract investors and raise capital. It’s targeted at VCs, fund managers, and founders. Drop me a line if this interests you and I’ll share details once it’s complete.

Until the next time,

Ben

This was great. "Don't deprive readers of the hard parts" is a directive I struggle with on Substack and in all online communication. The conventional wisdom for internet writing seems to be simplify, use lots of white space and short paragraphs, keep it quick. The medium doesn't seem equipped for "hard parts."