What Beethoven Has to Teach About Self Reinvention

Enacting heroism through music

I’ve been going through Robert Greenberg’s lectures on the Beethoven string quartets for the Great Courses series.

(By the way: if have not yet explored the Great Courses available at your local library, I highly recommend checking them out. These are under-celebrated treasures of 21st century American life.)

Greenberg explains Beethoven went through two wholesale self-reinventions in his life.

The first came after his early years.

A brilliant piano prodigy as a boy, he was driven by his alcoholic father to make money and tour in the manner of Mozart.

His early career as a composer he achieved renown as a composer and virtuoso.

After moving to Vienna, he dashed off dazzling improvisations and won favor among the aristocracy.

By 1802, however, he was in crisis. His hearing was in decline. The depression this caused was so severe that Beethoven retreated to a town outside Vienna and composed a confession and will addressed to his two brothers.

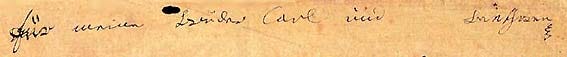

It is called The Heiligenstadt Testament.

…what a humiliation when one stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard the shepherd singing and again I heard nothing, such incidents brought me to the verge of despair, but little more and I would have put an end to my life - only art it was that withheld me, ah it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon me to produce, and so I endured this wretched existence

…

it was virtue that upheld me in misery, to it next to my art I owe the fact that I did not end my life with suicide

Instead of submitting to despair, Greenberg says, Beethoven decided to recreate himself as a hero.

He brought about this transformation not through warfare, but through his art.

To express this idea of himself as an undaunted soul, one who strives and ultimately overcomes torments in triumph, he had to craft an entirely new musical style.

From the 3rd Symphony (the Eroica) onward, Beethoven left behind the restraints of classical form in favor of a personal expressiveness that embodied this image.

He believed himself a hero, and through art he willed his heroism into existence.

Listening to the Eroica and the Razumovsky quartets gives you a feeling of this transformation.

The second transformation in Beethoven’s life is one I’ll revisit later. It’s what makes Beethoven still, to my ears, the most powerful and spiritually transcendental composer ever to live.

What I’m Reading

I once heard the researcher, author, and psychiatrist Ethan Kross asked what was the biggest misconception that he wished, as a scientist, to dispel.

His response was the pernicious idea that “venting” was good for you.

This writeup of his ideas from Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center is worth a read.

It turns out, however, that this type of emotional venting likely doesn’t soothe anger as much as augment it. That’s because encouraging people to act out their anger makes them relive it in their bodies, strengthening the neural pathways for anger and making it easier to get angry the next time around. Studies on venting anger (without effective feedback), whether online or verbally, have also found it to be generally unhelpful.

Over the weekend, I’d been thinking about how, as a father, it’s so critical to keep my temper in check.

The moment I relax my guard and let out a sharp tone, I find myself tumbling down a slope of increasing anger.

Like a flame, expressing the anger merely allows it to ignite.

When I posted about it on Twitter, I was surprised by the responses it generated.

What I’m Working On

The two lessons I’m preparing for the summer session of the Create, Publish, Profit program are coming along well.

I’m particularly eager to share my thoughts on how to get published in major media. It’s easier than you think, but like so many things, it just takes some insider knowledge to break through.

If you’re curious about that, the program is available here.

Hope your summer is going well.

Until the next time,

Ben